THE STORY Part 2

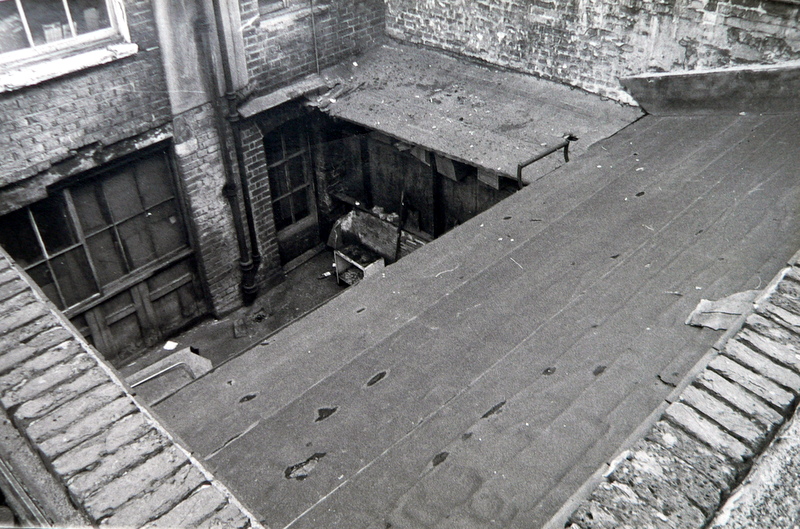

Personal circumstances saw me leaving Claybrook Road and somewhat desperate for somewhere to set up another workshop. After a couple of false starts I was pointed in the direction of 55, Marchmont Street, WC1. The lean-to building in the well of the back yard had formerly been used by Mick Casson before he moved to Hertfordshire.

The property was still owned by his brother Tony. I moved in. The rent was £1.00 per week. I don’t think Tony knew, but not only did I bring my kiln and wheel, but all my worldly goods, such as they were, in a rucksack. I had a couple of army surplus sleeping bags and slept under the wedging bench. As I heard the last train on the Piccadilly line rumble through, my ear close to the floor, I dreamt of moving out of London; space for a bigger workshop and a kiln with real fire.

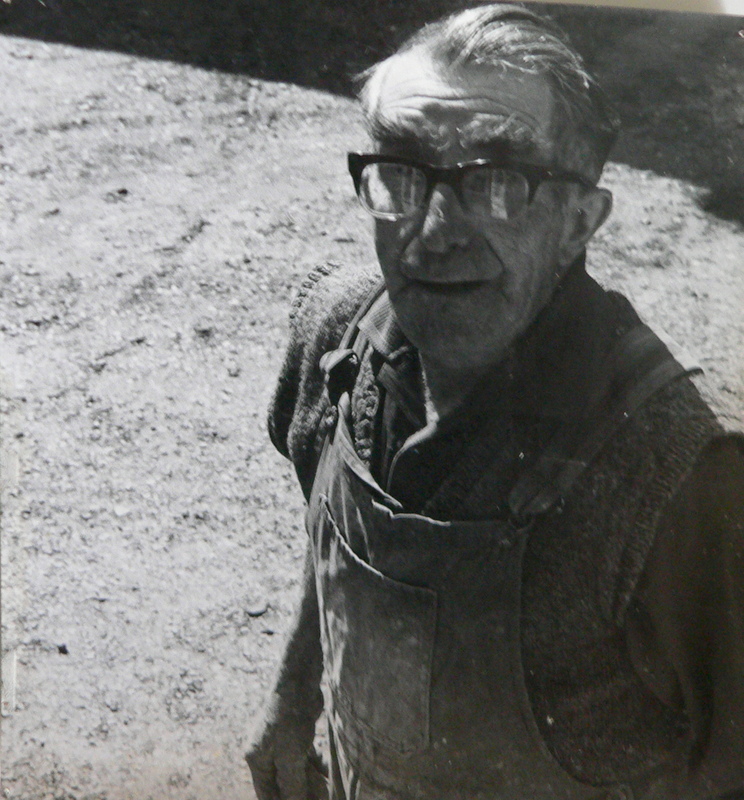

On the way back from a visit to Yorkshire, I had been to see Isaac Button, a remarkable old man, single handedly running the Soil Hill Pottery, I stopped by a roadside “For Sale” notice. It wasn’t eggs or cut flowers – it was a railway station near Peterborough. Closed in the 1930’s it had rustic charm and seemed like the ideal venue to start a pottery. It was to be auctioned in ten days time. Despite having saved every penny I could, plus a generous contribution from my Mum and the offer of a number of small loans I could not meet the selling price that was over one thousand pounds.

I then had a lucky escape. A schoolboy friend John Davidson also had ambitions about being a full time potter. Both of us hard up and looking for bigger workshop space we agreed we would go to a proposed craft community at the western tip of Scotland. For a short while it seemed like a good opportunity, but when I realised the distance involved I began to have doubts. John Davidson and I each had a weekend away. He went to the Cornwall and I went to East Anglia. We met on our return and both admitted shamefacedly that we didn’t want to go to the tip of Scotland. After anxious thoughts about letting each other down, we were both relieved.

I drew two concentric circles on a map of England, the centre being my current abode in London. Inside the first circle at 75 miles property would be too expensive to buy. Outside the second circle at 150 miles and I would be too far away from London where I expected to continue selling. I wrote to British Railways and asked them if they had any stations for sale in the Norfolk Broads area.

They didn’t want to sell me a station, but they had a couple of dilapidated railway crossing cottages in the middle of a field. I went to look – no mains water, no mains electricity, no road access, no good. Heading back to London I stopped in Stalham. I had parked in front of an empty Georgian house on the high street. I walked round the back and saw an enclosed yard with a two story outhouse come stable; perfect house and workshop. Encouraged to be adventurous by my wife to be I made enquiries. The local district council were keen to give me a fixed rate mortgage and to my stunned self I became a man of property.

It was named “Wisteria House” - perhaps because it had Wisteria, very pretty, growing so profusely, it had made its way into the roof. The removal of the offending flora and some essential repairs and the serious business of making pots had to be got under way. The premises provided ideal space for working and living.

There was no other income so it was do or die and it was almost the latter. The planned economy of the workshop was built around a new kiln which once installed failed to work. It ruined two thirds of every firing. I was making very expensive hand made hardcore. Every possible solution to solving the problem of the uneven heating of the kiln chamber was tried to no good end.

Almost broke and close to despair I went to the manufacturer of the kiln and said I wasn’t leaving until they gave me my money back. I survived on food parcels brought up from London by my future wife at the week ends. Another kiln from another firm and I got going. The first job was to establish a range of well designed pottery, repeatable, replaceable which would find a ready market in London.

What became known as the Stalham Standard Ware was quickly established. Mugs, jugs, bowls, plates, casseroles, coffee sets, salt jars, storage pots, whatever I could sell I was keen to make.

Everything was shipped down to London, principally to the CPA and Heals. I also began to supply smaller outlets in Norwich and around East Anglia. The efficient organisation of the workshop took shape and an ex bakery dough mixer and a pug mill were installed. Slowly the workshop got well organised, and the making of more ambitious individual pieces became a regular feature.

Further promotional exhibitions ensued, notably one sponsored by the Rural Industries Bureau at the Royal Norfolk Show. Also, to my surprise, as the spring of 1964 made early summer, Stalham became alive with tourists. A retail opportunity on the doorstep!

Quite soon the bulk of the pottery output was selling on site. I contemplated making a workshop open to the public, but decided I would not relish so much exposure and interruption. As a regular income became more settled I was able to give more time to making exhibition pieces.

The pottery was a busy place. I took on assistants who wanted to train while working. The need for a bigger kiln was clear and in 1966 I began planning to build an oil fired kiln. After visits to the workshops of David Eels, David Leach, Katherine Pleydell Bouverie and Ray Finch I decided to build a single chamber kiln similar to the one operated by David Eels.

Working with a local retired bricklayer, Billy Lake, the new kiln took shape.

I was anxious, operating beyond my experience, wondering if it would work. During the first firing I had used the wrong bricks to span the flue and they began to collapse causing the stacks of pots to lean over. Cones (temperature indicators) that were lined up with spy holes were no longer visible. You can’t open a kiln mid firing to have a look at what is going on. The opening, the moment of truth that every potter knows, is it success or failure? Many potters have caused damage by opening too soon, the thermal shock causing the pots to crack. This firing was good, the pots were well fired and except where the leaning stacks had touched and fused the pots together, it was otherwise all well. Relief and joy in equal measure.

With the rhythm of work established and the ordered supply of raw materials organised I found myself able to give time to developing my ideas. I had read widely and initially been much influenced by an essay by Harry Davis entitled “In Defence of the Rural Workshop” Inspired by a visit to his remarkable pottery in Praze, Cornwall the notion of making well designed domestic pottery took hold and much energy and thought went into that ideal.

Only later did I question the validity of such an approach. Was it necessary to turn oneself into some sort of automaton making an endless flow of repeated wares just to satisfy some post Arts and Crafts ideal? How did that sit in the second half of the twentieth century? On the other hand did the world need to groan under the weight of so many self indulgent products made by arty ceramists, epitomised by many of the works from around Europe in the Van Achterberg collection? At least the domestic pots had the virtue of being functional. These questions moved back and forth in my head. What I did know was that the energy demanded in running a busy workshop was more easily harnessed by having a clear notion of a working philosophy.

BACK TO TOP

I settled for what I still regard as a healthy duality. I would make repeatable domestic ware, but with a wide variety of glazes and treatments.

This constant practice of the relevant skills would then transfer to an easy facility when making the more ambitious ‘individual’ pieces. And so the work came in a steady stream. Each kiln load being a mixture of the ‘standard’ domestic ware and pots that were potentially suitable for exhibition. I developed many ‘slip’ glazes

from local Norfolk brick earths using early ordnance survey maps to locate them. The resultant glazes were rich in surface texture and depth. I also began to make a limited amount of porcelain.

My principal activity was the smooth running of Stalham Pottery and the production of pots as outlined above. However, like many creative people I found that I was interested in other media. I pursued photography and painting when I felt the need for a break from the perceived restrictions of the ceramics I had immersed myself in. In painting the surface has no practical function, ideas can be expressed in pure colour, narrative presents no problem. In photography I fed my interest in the landscape, object trouve and the recording of peoples lives. These wider interests enriched each other and prevented any sense of stagnating within one discipline. My exhibition at Castle Museum, Norwich sponsored by Sothebys showed these wider aspects of my work.

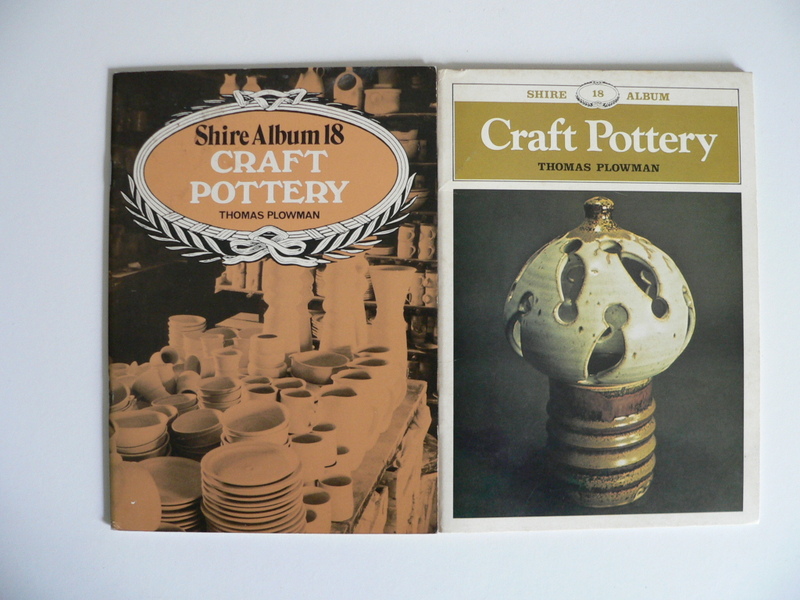

A glance at the list of individual exhibitions and group shows tells its own story. Taking part in a variety of group exhibitions including a British Potters Show in Kettles Yard Cambridge led to The Fitzwilliam Museum making a purchase for their permanent collection. While maintaining a steady ceramic output, I managed to fit in writing “Craft Pottery” for Shire Publications in 1976.

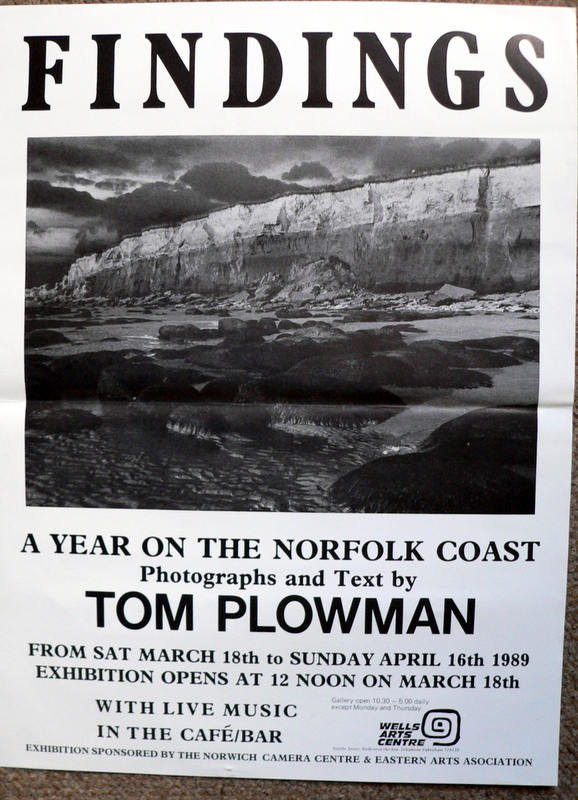

and later I took a year long look at the Norfolk coast resulting in an exhibition of photographs and extended text, sponsored by Eastern Arts, entitled “Findings” in 1989.

This led to setting up the photography department at Yarmouth College And teaching there. I continued at Stalham until 1991 a span of 27 years.

Fashions change and the general public became less interested in buying hand made domestic ware. I reduced the output and early in 1991 set up a new, smaller workshop in Catfield.

I quote from notes in my studio journal in April 1991 “some best quality one off pots and freedom to seek a wider audience for the ‘special’ stuff if and when it begins to emerge.”

Pretty soon after the move I began to make pots that were something of a departure from the main body of work of the last forty years. Over that period the work had undergone constant subtle changes and development. Now new shapes emerged with more playful forms, twisted handles and curled lids, some pieces were deliberately off centre.

A lot of the new work seemed to be challenging the standards to which I had always aspired. Even the surfaces changed. Earth colours gave way to subtle pinks and vivid blues. And then came a totally unexpected radical departure. I started making non functional pieces. Strange bird forms appeared with non ceramic attachments, beaten copper and silver, rope hair, gold paint.

I called them “Firebirds” - They were made mainly of a rougher textured fired clay, often using direct contact with smoke and flames, using some of the techniques of raku. Perhaps the location of my new, isolated workshop overlooking Catfield Fen had an effect on my thought processes.

As the new millennium approached I, once again, returned to the discipline of the classic vessel, but retaining some of the colour and features of the latter years. In 2006, the gas kiln I had been using was the worse for wear, I was seventy two and I considered we both needed a rest. Production of ceramics ceased.

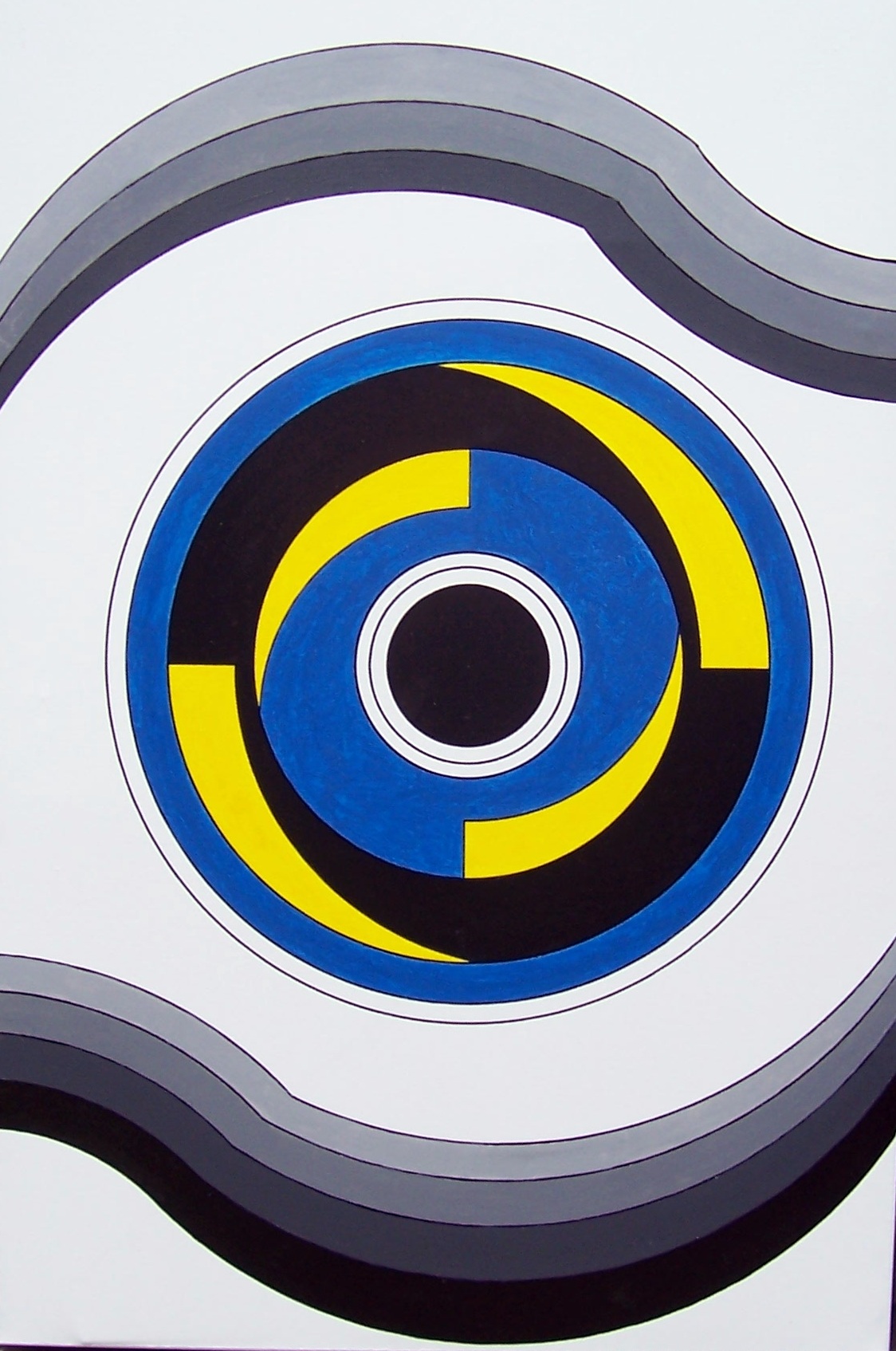

You can’t stifle the habits of a lifetime and so after a while I began doing some more painting

A return to and development of ideas that I had begun to explore during the 1950’s

Nine years elapsed with the kiln half filled with pots. In 2015 I decided to try my hand again and made enough pots to fill the kiln and fire it. I am not altogether sure it was a good idea because the kiln, already dilapidated had deteriorated further and a hole in the casing led to a fire. The wooden building in which the kiln was housed was burnt, but the pots survived intact. Since then I have rebuilt a small pottery workshop and intend to finish the cycle of making.

At 82 years of age I am uncertain of what I might make, perhaps a return to some earlier ideas, reworking them and exploring possibilities without any pressure to produce a viable result. I still retain some skills and have enough energy to prepare clay so…………………….. watch this space.